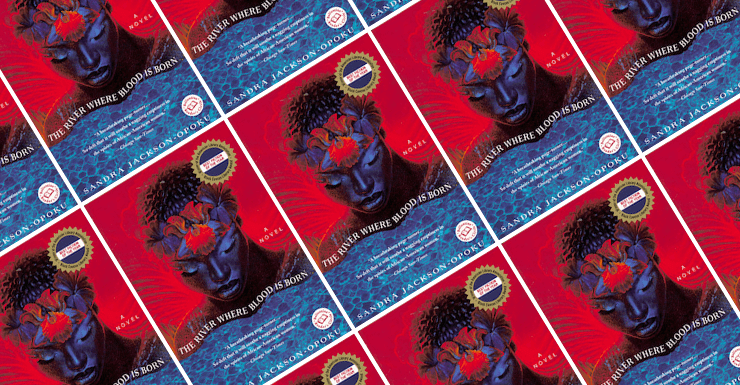

In 2016, Fantastic Stories of the Imagination published my survey “A Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction” (now hosted here). Since then Tor.com has published 21 in-depth essays I wrote about some of the 42 works mentioned, and another essay by LaShawn Wanak on my collection Filter House. This month’s column is dedicated to Sandra Jackson-Opoku’s award-winning epic The River Where Blood Is Born.

WINDING WAYS

Typical epics span centuries and nations—hemispheres, even. Not content with the limitations of those parameters, Jackson-Opoku takes us outside of time and beyond space as soon as her book begins. A village of disembodied women—ancestors and guardian spirits—gathers to judge River’s story, which is presented as the work of rival divinities: the Trickster and the Gatekeeper. These two weave real lives into a tapestry of a tale in which nine generations descended from a once-sterile woman wander far from their lost African home. Thus the novel is put immediately into a fantastic frame of reference.

The prodigal daughters’ journeying begins in the 18th century with the exile of an Ashanti chief’s wife, followed soon after by the kidnapping and enslavement of her beautiful offspring, Ama. Ama’s tongue is cut, rendering her speech unintelligible and her origins inscrutable. Questions roil the dissatisfied souls of all her lineage. Sometimes without even knowing what they’re asking, they seek answers. From a Caribbean plantation to the shores of the Illinois River to the steep streets of Montreal to quiet Ghanaian beaches cradling lovers in their sandy embrace, through coincidences and missed connections and determination and dreams, River rolls on its unpredictable yet steady course, ending where it began.

WALKING SCIENCE FICTION

Once again, as in last month’s column, I invoke the wisdom of Walidah Imarisha’s pronouncement that we are “walking science fiction”—that is, that we represent the fulfillment of our ancestors’ collective wishes. River perfectly illustrates this concept. The women dwelling in the otherworldly village—an imaginary location Jackson-Opoku depicts throughout her novel at strategic intervals—long for the fresh perspectives and sustenance that can be brought to them by their living relatives. They envision an eventual understanding and acceptance of their role, new petitions from mortals for their immortal assistance, dedicated followers, restoration to their former glory.

Modern Africans and members of the African diaspora participate in this project of honoring our past thoughtfully, continually, with joy and grace. One way we participate is by reading books like River, books which show how our reclaimed past braids into an imagined inclusive future.

WAIT A MINNIT

Not everybody in Jackson-Opoku’s village of ancestor spirits agrees on where they are, what they’re doing, to whom they owe their allegiance, or how they’re going to get the good things they deserve, though. A Christian arrives expecting angel wings. A loose-hipped “hoochie mama” crashes in declaring that “Death ain’t nothin’ but a party!” And a biological male has the nerve to ask for admission to the all-female enclave on the grounds that he was his child’s true mother.

Similarly, students of Black Science Fiction have our controversies. Who is Black? Who’s African? What’s “science,” and what’s its role in the stories we tell? Who gets to tell them?

In the multi-voiced, rainbow-hued literary kente cloth of her novel, Jackson-Opoku recreates the diversity of African-derived culture, a whole which has never been a monolith. To start with, Africa is a continent, not a country: Languages, landscapes, and histories vary from one nation to another. To go on, some left. Some stayed. Add to those fundamental distinctions others along other axes: age, gender, sexuality, disability… no wonder there’s no single, totalizing “African experience” for an author to represent. Instead, River shows us how our differences give rise to beautiful harmonies and enrapturing syncopation.

WHERE WE COME FROM

Over twenty years ago, when this, her first novel was first published, Jackson-Opoku revealed to interviewers and reviewers that River had been inspired by a trip to Africa she made in 1975. She said she had spent the two decades since writing it.

Buy the Book

Does humankind originate in Central Africa, as has been theorized? Recent research complicates the answer, but one thing’s clear: many of our ancestors called that continent home over a very, very long time. And plenty of educational and technological innovations can also claim African origins.

It makes sense that the homeward quests of Ama’s furthest flung generations focus on The Continent. And analogizing from the novel it makes sense that, when seeking Black science fiction’s inspiration, we focus on the many locations, legends, and lessons Mama Afirika offers us. The controversies I mention up above include the definition of Afrofuturism. Since the Black Panther movie, especially, that term is being applied to lots and lots of Black-oriented speculative fiction. But what is Afrofuturism, actually? Is it an aesthetic? A marketing category? Does the second of its root words refer to a true, temporal future, or only to a futuristic feeling? What about that first root word—does that make the term the rightful territory of Africans or Afrodiasporans? Or both?

We don’t always agree on the answers to these questions, but we get excited whenever we find one that seems a possible fit. We like looking for them.

WELL THEN

The River Where Blood Is Born is both a complex narrative and a straightforward metanarrative about being lost and found. It tells us how its individual characters restore their roots while modeling the inclusiveness and Afrocentrism necessary to a successful Black SF movement. Read it for pleasure. Read it for knowledge. Read it to keep up with the rest of us: we who are already heading upstream toward the source of its fabulation.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Every time you post, I find another great book to read- thanks!

You’re welcome! That’s kinda my job.